A Massachusetts minimum-wage increase would help working families and generate jobs

By Mary Gable

August 21, 2012 - Economic Policy Institute

Issue Brief #340

The Massachusetts minimum wage is currently $8.00 per hour, and a proposal to

increase it to $10.00 is before the state legislature.

Amid persistently high unemployment and the resulting downward pressure on

wages, increasing the statefs minimum wage would provide a welcome lift to the

Massachusetts economy. An increase would also help working families in

Massachusetts make ends meet in the aftermath of the worst recession in

generations.

This issue brief explains why raising Massachusettsfs minimum wage would be a

tool for economic growth and examines the magnitude of these positive economic

effects. Key findings include:

- If enacted on January 1, 2013, a minimum-wage increase in Massachusetts to

$10.00 per hour would give more than 581,000 of the statefs lowest-paid

workers a raise.

- Raising the statefs minimum wage would increase wages by almost $824

million for directly and indirectly affected workers.

- The increase would create roughly 4,500 net new jobs within the first

year.

Raising the minimum wage as a tool for economic growth

The immediate benefits of a minimum-wage increase are in the boosted earnings

of the lowest-paid workers, but its positive effects would far exceed this extra

income. Recent research reveals that, despite skepticsf claims, raising the

minimum wage does not cause job loss.

In fact, in Massachusetts and other states, minimum-wage increases would

create jobs. Like unemployment insurance benefits or tax breaks for

low- and middle-income workers, raising the minimum wage puts more money in the

pockets of working families when they need it most, thereby augmenting their

spending power. Economists generally recognize that low-wage workers are more

likely than any other income group to spend any extra earnings immediately on

previously unaffordable basic needs or services.

Increasing Massachusettsfs minimum wage to $10.00 on January 1, 2013, would

give a raise to more than 581,000 of the statefs lowest-paid workers.

It would provide nearly $824 million in additional wages

to directly and indirectly affected families, who would, in turn, spend those

extra earnings. Indirectly affected workers—those earning close to, but still

above, the proposed new minimum wage—would likely receive a boost in earnings

due to the gspilloverh effect (Shierholz 2009), giving them more to spend on

necessities.

This projected rise in consumer spending is critical to any recovery,

especially when weak consumer demand is one of the most significant factors

holding back new hiring (Izzo 2011).

Though the stimulus from a minimum-wage increase is smaller than the boost

created by, for example, unemployment insurance benefits, it is still

substantial—and has the crucial advantage of not imposing significant costs on

state governments. Thus, a minimum-wage increase is one of the few

budget-neutral ways for state governments, already struggling with budget

shortfalls, to give a shot in the arm to the economy.

Assessing the job creation effects of a minimum-wage increase

In addition to providing a wage increase to hundreds of thousands of

Massachusetts workers, raising the statefs minimum wage would create jobs.

Showing that raising the minimum wage would be a tool for modest job creation

requires an examination of the stimulative effects of minimum-wage increases.

Because minimum-wage increases come from employers, we must construct a

gminimum-wage increase multiplierh that takes into account the increase in

compensation to low-wage workers and the decrease in corporate profits that both

occur as a result of minimum-wage increases. Raising the minimum wage means

shifting profits from an entity (the employer) that is much less likely to spend

immediately to one (the low-wage worker) that is more likely to spend

immediately. Thus, increasing the minimum wage stimulates demand for goods and

services, leading employers in the broader economy to bring on new staff to keep

up with this increased demand.

When economists analyze the net economic stimulus effect of policy proposals

(e.g., tax rate changes that boost income for some and reduce it for others),

they use widely accepted fiscal multipliers to calculate the total increase in

economic activity due to a particular increase in spending. In applying these

multipliers, economists generally recognize a direct relationship between

increased economic activity and job creation. This analysis assumes that a

$115,000 increase in economic activity results in the creation of one new

full-time-equivalent job in the current economy.

Using these same standard fiscal multipliers to analyze the jobs impact of an

increase in compensation of low-wage workers and decrease in corporate profits

that result from a minimum-wage increase, we find that increasing the

Massachusetts minimum wage from $8.00 to $10.00 per hour would result in a net

increase in economic activity of approximately $522 million and would generate

roughly 4,500 net new jobs (see Appendix for methodological details).

Though this would not return the statefs unemployment rate to pre-recession

levels, it would be a substantial boost to the Massachusetts economy.

The benefits of a minimum-wage increase in an economic downturn

Examining the positive effects of a minimum-wage increase in Massachusetts

leads to an overarching discussion of the economic case for increasing the

earnings of the lowest-paid workers during an economic downturn. In the current

economic climate, nearly everything is pushing against wage growth. With 3.4

unemployed workers for each job opening (Gould 2012), employers do not have to

offer substantial wages to hire the workers they need, nor do they have to pay

substantial wage increases to retain workers.

It is important to note that despite the weak overall condition of the U.S.

economy, corporations can afford to increase the wages of the lowest-paid

workers. Since 1973, corporate profits have continued to soar as American

workers have become more productive. Corporate America even has recovered the

losses of the 2008 crash, with profits once again growing much more quickly than

productivity and wages. Yet in Massachusetts and nationwide, most

workers—especially the lowest-paid workers—have not shared in this prosperity.

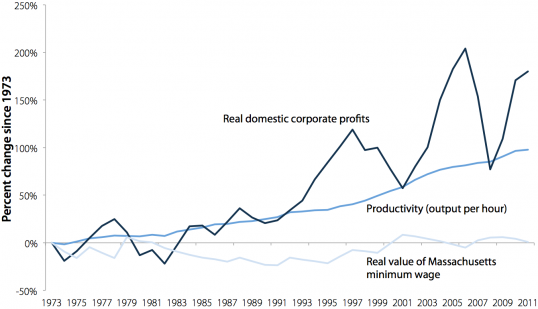

Figure A reveals this disconnect. It shows that real corporate

profits peaked in 2006 at more than 200 percent growth since 1973, while the

real value of the Massachusetts minimum wage in 2011 was just 1 percent higher

than in 1973. Meanwhile, workersf productivity increased almost 100 percent

during the same period. Increasing the minimum wage in Massachusetts would help

raise the lowest-paid workersf earnings to reflect their increased

productivity.

Figure A

Change in productivity, corporate profits, and the Massachusetts

minimum wage, 1973–2011

Source: Author's analysis of data from the U.S.

Department of Labor, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the Bureau of

Economic Analysis

Even conservative economists suggest higher wages might help speed the

recovery. American Enterprise Institute scholar Desmond Lachman, a former

managing director at Salomon Smith Barney, told The New York Times,

gCorporations are taking huge advantage of the slack in the labor market—they

are in a very strong position and workers are in a very weak position. They are

using that bargaining power to cut benefits and wages, and to shorten hours.h

According to Lachman, that strategy gvery much jeopardizes our chances of

experiencing a real recoveryh (Powell 2011).

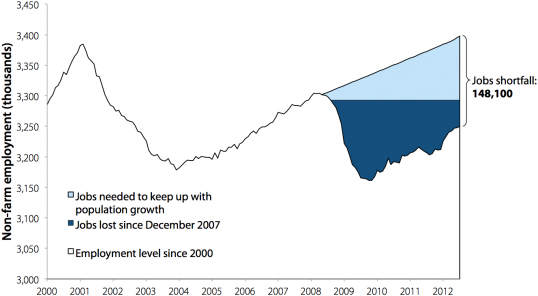

Furthermore, the national unemployment rate is currently 8.3 percent and is

not expected to return to pre-recession levels for several years. In

Massachusetts, the unemployment rate is 6.1 percent and, as Figure

B shows, the statefs gjobs shortfall,h or the difference between the

number of jobs Massachusetts has and the number necessary to return to the

pre-recession unemployment rate, is 148,100. That number includes the 43,500

jobs Massachusetts has lost since December 2007 plus the 104,600 jobs it would

have needed to add to keep up with the 3.2 percent population growth the state

has experienced in the 55 months since the recession began.

To close this gap within three years, Massachusetts would have to create 5,500

new jobs every month. In the past year, Massachusetts has added 42,800 jobs,

enough to cover less than eight monthsf worth of necessary growth. At that rate,

it would take Massachusetts more than three years to return to the pre-recession

unemployment rate. Considering the past yearfs sluggish job growth rate, a

minimum-wage increase that creates about 4,500 net new jobs would help

strengthen the recovery.

Figure B

Massachusetts jobs shortfall, January 2000–July 2012

Source: Author's analysis of Bureau of Labor

Statistics Current Population Survey, Current Employment Statistics, and

Local Area Unemployment Statistics data

Conclusion

The multiple positive effects that would result from a higher minimum wage in

Massachusetts are clear: It would boost the earnings of working families hardest

hit by the Great Recession, spur economic growth, and create about 4,500 net new

jobs. In an economic climate in which wage increases for the most vulnerable

workers are scarce, raising the minimum wage to $10.00 is an opportunity that

working families in Massachusetts cannot afford to lose.

Appendix: Methodology

An analysis of the stimulative impact of raising the minimum wage in

Massachusetts draws on the macroeconomic multipliers calculated by Moodyfs

Analytics Chief Economist Mark Zandi (2011), which estimate the one-year dollar

change in gross domestic product (GDP) for a given dollar reduction in federal

tax revenue or increase in spending. Averaging the stimulus multipliers of the

Earned Income Tax Credit (within the parameters of the American Recovery and

Reinvestment Act, or ARRA) and Making Work Pay (ARRAfs refundable tax credit for

working individuals and families) gives a reasonable fiscal stimulus multiplier

for the spending increase due to the increase in compensation of low-wage

workers. This value is 1.2, which means that a $1 increase in compensation to

low-wage workers leads to a $1.20 increase in economic activity.

The calculation of the stimulative impact of the minimum wage, however, must

also account for the offsetting shift from employers. We assume employers pass

on some of the minimum-wage increase to consumers through increased prices

(somewhere between 20 percent and 50 percent). Thus, we calculate the offsetting

multiplier effects as a weighted average of Zandifs multiplier for an

across-the-board tax cut (1.04, as a proxy for increased prices) and a cut in

the corporate tax rate (0.32).

The minimum-wage multiplier is between:

1.2 MW consumer spending increase multiplier – [0.32 corporate tax rate

cut*(1-0.5 price pass-through) + (1.04 across-the-board tax cut*0.5 price

pass-through)] = 0.53

(representing the case where 50 percent of the minimum-wage increase is

passed through to prices)

and

1.2 MW consumer spending increase multiplier – [0.32 corporate tax rate

cut*(1-0.2 price pass-through) + (1.04 across-the-board tax cut*0.2 price

pass-through] = 0.74

(representing the case where 20 percent of the minimum-wage increase is

passed through to prices).

Taking into account the fiscal stimulus multiplier range of the minimum-wage

increase (0.53 to 0.74) and the increased wages (gwage bill increaseh) of

directly affected workers, we can calculate the GDP impact of the proposal to

increase Massachusettsfs minimum wage to $10.00.

The GDP impact is between:

$823,911,180 wage bill increase*0.53 minimum-wage multiplier (low) =

$432,553,370 GDP impact (low)

and

$823,911,180 wage bill increase*0.74 minimum-wage multiplier (high) =

$610,518,184 GDP impact (high).

We use the general rule that it takes a GDP increase of $115,000 to create

one full-time-equivalent (FTE) job and a GDP increase of $127,000 to create a

payroll job. Then, calculating the impact of an increase in the Massachusetts

minimum wage to $10.00 on January 1, 2013, the number of FTE jobs created is

between:

$432,553,370 GDP impact (low)/$115,000 GDP increase per FTE job = 3,761 FTE

jobs

and

$610,518,184 GDP impact (high)/$115,000 GDP increase per FTE job = 5,309

FTE jobs.

The number of payroll jobs created is between:

$432,553,370 GDP impact (low)/$127,000 GDP increase per payroll job = 3,406

payroll jobs

and

$610,518,184 GDP impact (high)/$127,000 GDP increase per payroll job =

4,807 payroll jobs.

Full-time-equivalent job measurements take into account both the increase in

the number of payroll jobs and the increase in work hours for those who already

had jobs by calculating the equivalent number of 40-hour-per-week jobs that

would be created by the GDP boost. Measuring the number of payroll jobs strictly

shows the number of jobs (not measured by hours). Thus, an increase in the

minimum wage in Massachusetts to $10.00 on January 1, 2013, would create, over

one year, a conservative estimate of roughly 4,500 jobs (whether measuring FTE

or payroll).

Endnotes

A proposal (S. 951) to increase the Massachusetts minimum wage to $10.00

per hour over two years passed the statefs Joint Committee on Labor and

Workforce Development in March 2012 and is currently before the legislature.

This analysis instead assumes an increase in the minimum wage to $10.00 goes

into effect on January 1, 2013.

See the recent EPI paper The benefits of raising Illinoisf minimum

wage: An increase would help working families and the state

economy (Hall and Gable 2012) for a description of the definitive

studies on minimum-wage increases and the absence of disemployment effects.

According to the authorfs analysis of 2011 Current Population Survey

Outgoing Rotation Group microdata. This total includes directly affected workers

(those who would see their wages rise because the new minimum wage would exceed

their current hourly pay) and indirectly affected workers (those who would

receive a raise as employer pay scales are adjusted upward to reflect the higher

minimum wage).

According to the authorfs analysis of 2011 Current Population Survey

Outgoing Rotation Group microdata. This analysis assumes 0.4 percent population

growth (the Massachusetts projected annual average growth rate from 2000 to

2020, according to the U.S. Census Bureau). The model assumes no wage growth

from 2011 survey values prior to the proposed minimum-wage increase on January

1, 2013. The increased wages are the annual amount of increased wages for

directly and indirectly affected workers, assuming they work 52 weeks per

year.

In a recent poll of 53 economists by The Wall Street Journal,

the majority (65 percent) cited a lack of demand as the main reason for a lack

of new hiring by employers (Izzo 2011).

A recent analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities projects a

$1.3 billion budget shortfall in Massachusetts in fiscal year 2013. At 3.8

percent of the general fund budget, this shortfall is much smaller than those of

the states with the most severe budget gaps. However, it could cause the state

to cut government services and public-sector jobs at a time when doing so would

be particularly harmful to the economy (McNichol et al. 2012).

In a paper on the methodology used to estimate the jobs impact of various

policy changes, the Economic Policy Institutefs Josh Bivens found that $115,000

in additional economic activity results in the creation of one new

full-time-equivalent job, and $127,000 in additional economic activity results

in the creation of one new payroll job (Bivens 2011).

According to the authorfs analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing

Rotation Group microdata and Zandi (2011).

This calculation uses Current Employment Statistics and Local Area

Unemployment Statistics data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It provides an

estimate in line with EPIfs national-level estimate of the jobs shortfall, which

combines Current Employment Statistics and Current Population Survey data. This

estimate is based on the dates of the national recession, not those of the

Massachusetts recession.

While this paper presents multipliers rounded to two decimal places, the

calculations use the exact multiplier.

References

Bivens, Josh. 2011. Method Memo on Estimating the Jobs Impact of Various

Policy Changes. Economic Policy Institute.

http://www.epi.org/publication/methodology-estimating-jobs-impact/

Bureau of Economic Analysis. Various years. National Income and Product

Accounts Tables, Tables 6.16B, 6.16C, and 6.16D, gCorporate Profits by

Industry,h Excel spreadsheets accessed August 2012.

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=9&step=1

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Various years. Data, Tables & Calculators

by Subject, gMajor Sector Productivity and Costs,h Excel spreadsheets

accessed August 2012. http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/PRS85006092

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Current Employment Statistics program. Public

data series. Various years. Employment, Hours and Earnings-State and Metro

Area [database]. http://www.bls.gov/sae/

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Local Area Unemployment Statistics program.

Public data series. Various years. Local Area Unemployment Statistics

[database]. http://www.bls.gov/lau/#data

Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata. Various years.

Survey conducted by the Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics

[machine-readable microdata file]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

http://www.bls.census.gov/cps_ftp.html#cpsbasic

Gould, Elise. 2012. gJob Seekersf Odds Improve but Remain Slim.h Economic

Policy Institute JOLTS report, August 7.

http://www.epi.org/publication/job-seekers-odds-improve-remain-slim/

Hall, Doug, and Mary Gable. 2012. The Benefits of Raising Illinoisf

Minimum Wage: An Increase Would Help Working Families and the State

Economy. Economic Policy Institute, Issue Brief #321.

http://www.epi.org/publication/ib321-illinois-minimum-wage/

Izzo, Phil. 2011. gDearth of Demand Seen behind Weak Hiring.h The Wall

Street Journal, July 18.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303661904576452181063763332.html

McNichol, Elizabeth, Phil Oliff, and Nicholas Johnson. 2012. States

Continue to Feel Recessionfs Impact. Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities. http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=711

Powell, Michael. 2011. gCorporate Profits Are Booming. Why Arenft the Jobs?h

The New York Times, January 8.

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/09/weekinreview/09powell.html

Shierholz, Heidi. 2009. Fix It and Forget It: Index the Minimum Wage to

Growth in Average Wages. Economic Policy Institute, Briefing Paper #251.

http://www.epi.org/publication/bp251/

U.S. Department of Labor. Various years. State Labor Laws Historical

Tables, gChanges in Basic Minimum Wages in Non-farm Employment Under State

Law: Selected Years 1968–2012,h last revised December 2011.

http://www.dol.gov/whd/state/stateMinWageHis.htm

U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Population Projections. 2000–2012. Population

Pyramids and Demographic Summary Indicators for States. Excel spreadsheets

accessed July 2012.

http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/statepyramid.html

Zandi, Mark. 2011. gAt Last, the U.S. Begins a Serious Fiscal Debate.h

Dismal Scientist (Moodyfs Analyticsf subscription-based website), April

14.

http://www.economy.com/dismal/article_free.asp?cid=198972&tid=F0851CC1-F571-48DE-A136-B2F622EF6FA4